The Boston Globe has named A Labyrinth of Kingdoms one of 2012’s eleven best books of nonfiction, putting it in some distinguished company. I’m honored.

Tag Archives: exploration

August Petermann, Cartographer of Exploration

Heinrich Barth’s invitation to join the British expedition can be traced back to a German cartographer named August Petermann. Petermann was working at the London Observatory when he heard about James Richardson’s proposed African expedition and its need for a scientist. Petermann told Chevalier Bunsen, the Prussian ambassador to the Court of St. James’s, who approached Richardson and offered to find him the best available German scientist. Richardson was delighted, since Germany’s scientists were considered the finest in Europe. Carl Ritter and Alexander von Humboldt, eminences at the University of Berlin, recommended Barth.

August Petermann

From the start, Petermann took a keen, almost proprietary, interest in the expedition. He became an important long-distance affiliate and cheerleader. He lobbied the British Foreign Office to send more funds and helped to arrange for another German scientist, Eduard Vogel, to join the expedition. When Barth sent rough maps and measurements of the mission’s routes back to Britain, the Foreign Office hired Petermann to turn them into works of cartography.

All this was fine, but in his over-enthusiasm Petermann also sent his maps to German publications, along with information from Barth’s dispatches. This did not sit well with some people at the FO and the Royal Geographical Society, and fed the resentment against Germany in some British quarters that I described in an earlier post.

All this was fine, but in his over-enthusiasm Petermann also sent his maps to German publications, along with information from Barth’s dispatches. This did not sit well with some people at the FO and the Royal Geographical Society, and fed the resentment against Germany in some British quarters that I described in an earlier post.

“Of course it is Mr. Petermann’s object,” wrote the FO under-secretary, “to make himself, for his own profit, and also for his own glory, the historiographer of all the discoveries of Barth and Overweg: but that is not our object, or intention . . . Drs. Barth and Overweg were members of Richardson’s expedition, paid by us, and traveling at our expense,” he continued, and any public announcements about the expedition should come from the Royal Geographical Society, “which properly speaking is our natural medium of partial geographical communications.”

Petermann and Chevalier Bunsen, he added, seemed to consider the British “the mere paymasters of the expedition, while the fruits belong to Germany. This is a mistake.”

The secretary of the RGS expressed his irritation more crudely, writing about the expedition in the society’s journal, “In connection with Lake Chad and other African names, it may be observed that the Germans are adopting various ways of spelling them, because they find it difficult to say ‘cheese.’”

This was too much for Petermann. He responded with a nine-page open letter that called the RGS report “scurrilous and offensive.”

When Barth returned to England, he stepped into this stew. Under questioning from the RGS and the FO, he agreed that Petermann sometimes published information about the mission too hastily, but added that he was motivated by his scientific eagerness to share information, not by German nationalism.

Barth admired Petermann’s passion for exploration and his exquisite skills as a cartographer. (Petermann’s numerous maps are one of the glories of Barth’s book. See examples here, here, and here.) Petermann was also indirectly responsible for the book’s wonderful illustrations. He recommended that Barth hire the German artist J. M. Bernatz, who turned Barth’s sketches into the book’s many finished drawings.

Barth’s entry into Timbuktu

But the cartographer sometimes exasperated the explorer. Barth once wrote, “I believe Petermann has really convinced himself that the African expedition was his work, not mine, and that Providence only brought me safely through all those unspeakable dangers thanks to his ideas and his leadership abilities. . . . Despite his great and justifiably rewarded abilities, Petermann is a real loudmouth.”

Petermann returned to Germany in the mid-1850s and continued to publish extraordinary maps based on discoveries by explorers all over the globe. In appreciation, explorers named geographic features on several continents after him. His devotion to exploration and meticulous cartography is his enduring legacy.

His personal life, however, was evidently unhappy, and he may have been a manic-depressive. In October of 1878, aged 56, he killed himself with a pistol.

—–

In other news, A Labyrinth of Kingdoms was last week’s “Book of the Week” in The Times of London, which gave it an enthusiastic review (restricted access): A Labyrinth of Kingdoms by Steve Kemper.

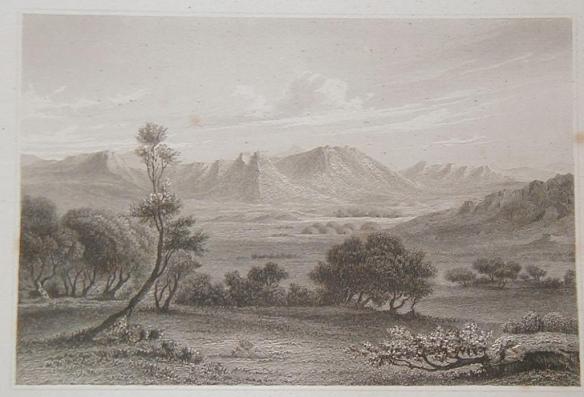

The Hill of the Christians

One of the most fascinating and perilous segments of Barth’s journey occurred in the district of Aïr in the Sahara, in present-day Niger. About 300 miles long and 200 miles wide, Aïr consists of steep disconnected massifs and volcanic cones, some rising more than 6,000 feet from the desert floor. Barth called it “the Switzerland of the desert.” Until he described it, Europeans were unaware that the Sahara contained such landscapes. Before Barth’s party entered the region, no European had ever set foot there. European visitors would be extremely rare for many decades afterwards.

The landscape of Aïr. From Travels and Discoveries.

In Barth’s day, Aïr was an isolated redoubt occupied by gangs of Tuareg brigands who had never been subdued by an outside power. This remained true, off and on, for next 150 years. I had hoped to visit Aïr while researching my book, but the district was off-limits to travelers because Tuareg rebels had a base there.

At the time of Barth’s journey, the capital of Aïr was Tintellust, deep in the region’s heart. Barth’s group reached there soon after being plundered and nearly murdered by Tuaregs in Aïr. The Europeans expected Tintellust to be a city, but it turned out to be a village of 250 dwellings shaded by trees in a pleasant mountain valley. The explorers weren’t too disappointed, because for the first time in weeks they felt safe. Tintellust was the home of Sultan Annur, leader of the Kel Owis, a Tuareg tribe. For a large sum, Annur agreed to protect the expedition.

Annur told the Christians to camp at a spot 800 yards from the village on some sand hills. The location offered sweeping views of the valley and the mountains. Barth predicted that the place would henceforth be called the “English Hill” or the “Hill of the Christians.”

Tintellust

Francis Rennell Rodd, a British explorer, traveled in Aïr in the 1920s and wrote a wonderful book about it called People of the Veil. Rodd found Aïr and its Tuareg inhabitants exactly as Barth had described them 75 years earlier. I especially like Rodd’s description of male Tuaregs: “The men never grow fat: they are hard and fit and dry like the nerve of a bow, or a spring in tension. Of all their characteristics the one I have most vividly in mind is their grace of carriage. The men are born to walk and move as kings, they stride along swiftly and easily, like Princes of the Earth, fearing no man, cringing before none, and consciously superior to other people.” Their belligerence and opportunism, noted Rodd, hadn’t changed either, as expressed in one of their sayings: “Kiss the hand you cannot cut off.”

Rodd wanted to visit Tintellust to look for traces of Barth, whom he called “perhaps the greatest traveler there has ever been in Africa.” Tintellust wasn’t on any map, but Rodd’s guide knew the village and took him there. As they reached the outskirts, the guide pointed out a place called “the House of the Christians.” When Rodd asked why, the guide said that in the olden days three white Christians who weren’t French had come to Tintellust—not as conquerors, like the French, but as friends of Chief Annur—so the thatch huts where they camped had never been inhabited or pulled down. All that remained of the camp, noted Rodd, were “the traces of two straw huts and a shelter, a wooden water trough, and some broken pots.”

In 2005 Julia Winckler, a British photographer and teacher fascinated by Barth, traveled to Tintellust. She too was shown Barth’s old encampment. She documented her visit to Tintellust (and Agadez) with photographs and videos: www.retracingheinrichbarth.co.uk. In Tintellust, according to Winckler, a story persists that Barth buried treasure nearby, and the villagers occasionally still dig for it. Barth would be amused–by the time he and his ragged group reached Tintellust, they had been pillaged several times and had no surplus to bury.

Weird White Men

European explorers went to Africa certain that they carried the banner of civilization and were superior to the natives, whose skin, after all, was dark, and whose fashions and physiognomies often didn’t conform to European models. To some explorers, and to many Europeans who came later, white was right and dark was ugly, barbaric, pitiable.

Africans had a different point of view. The early European explorers often found the tables turned—they were the ones pitied as ugly and barbaric. They were infidels with white skin–unenlightened, unsightly, pathetic. Africans stared at them as if they were circus freaks, sometimes with fright, sometimes with derisive laughter. At first this inversion shocked and sometimes offended the explorers, but most of them soon found it amusing.

Mungo Park

Mungo Park, for instance, was required to display his pale skin several times during his travels through the Gambia, usually for inquisitive women. One group of them asked for visual proof of his circumcision.

Dixon Denham and Hugh Clapperton, who preceded Barth to Bornu in the 1820s, also attracted many inquisitive women, who investigated these white oddities by rubbing their unappealing pasty skin and touching their weirdly-textured hair. “Again,” wrote Denham, “my excessive whiteness became a cause of both pity and astonishment, if not disgust; a crowd followed me through the market, others fled at my approach; some of the women oversetting their merchandize, by their over anxiety to get out of my way. . . . One little girl was in such agonies of tears and fright, at the sight of me, that nothing could console her, not even a string of beads which I offered her—nor would she put out her hand to take them.”

One evening as Denham passed three women in the street, they stopped to question him about why he was there. They also asked, “Is it true that you have no khadems, female slaves? No one to shampoo you after a south wind?” Yes, said Denham, explaining that he was far from home and alone. No, retorted one of the women, you are an infidel and a hyena who eats blacks. His only hope of becoming civilized, continued the women, was to marry a wife or two who would teach him to pray and wash “and never let him return amongst his own filthy race.”

Clapperton related similar encounters. After three of a governor’s wives examined his skin closely they “remarked, compassionately, it was a thousand pities I was not black, for I had then been tolerably good-looking.” When he asked one of them, “a buxom young girl of fifteen, if she would accept of me for a husband . . . She immediately began to whimper; and on urging her to explain the cause, she frankly avowed she did not know how to dispose of my white legs.”

Sheikh al-Kanemi

Some Africans suspected Denham and Clapperton of being monsters and cannibals—another inversion of common white attitudes about blacks. No wonder that when Sheikh al-Kanemi, the ruler of Bornu, publicly shook hands with Denham and Clapperton, his courtiers gasped at his bravery for touching these mutants. Another inversion.

Barth and his companions ran into the same things. When the young boy Dorugu first saw Overweg, who bought and freed him, Dorugu was appalled that Overweg’s “face and hands were all white like paper,” and he feared that this stranger was going to eat him.

James Richardson

After months of travel Barth turned as dark as an Arab (and eventually passed himself off as a Syrian sherif). But Richardson disliked the sun and was careful to keep his skin pale. Consequently he often attracted laughing crowds and was sometimes advised to let his skin darken so he wouldn’t look so disgustingly white—a telling inversion of the old advertisements once aimed at dark-skinned people to improve their looks by bleaching their skin.

Into the Desert

To gather sensory information about Barth’s travels, I wanted to spend a day on a camel in the desert. Shindouk arranged it. One morning a Tuareg wearing blue robes and a long sword showed up at the hotel’s gate. Somber and unsmiling, he was riding a white mehari and leading another. His name was Agali ag-Mohamed, Ali for short. Shindouk told me was a Kel Ulli, a tribe in the Imrad class of Tuaregs.

Ali on his mehara

All this fascinated me. Mehara, for instance, are the fast slender breed long favored by desert raiders such as the Tuaregs. The Imrad are the vassal class of Tuaregs (all Tuaregs belong to one of three classes: nobles (Ihaggaren), vassals, or slaves). I knew of the Kel Ulli because they had helped Barth in Timbuktu. He described them as ferocious warriors, infamous for “totally annihilating” two other powerful Tuareg tribes.

I climbed onto the prone mehara. At a signal from Ali, it sharply lifted its hind legs, almost pitching me headfirst into the sand. Lesson number one. Lesson number two came later, in reverse, when Ali gave the signal to lie down and my camel suddenly tilted onto its front knees, nearly launching me again.

Tuaregs use a U-shaped wooden saddle, covered with sewn goatskin, that sits in front of the hump. They ride with both bare feet resting on the left side of the camel’s neck. I mimicked Ali. At the edge of town we stopped so he could buy a new SIM card for his cell phone, which he tucked beneath his blue robes.

Acacia thorn

I enjoyed the rocking gait of the camel. The desert was greener than I expected, with grasses, bushes, and stunted trees, such as the lovely but vicious acacia, with its red bark, frilly green leaves, and long silver thorns. About an hour into the journey I became acquainted with another desert plant. I dismounted (voluntarily, shortly after learning lesson number two) to walk to a place for a photo. Within 10 yards my shoeless feet felt as if they getting stung by a mob of ground hornets.

“Kram-kram,” said Ali without interest. Kram-kram is a patchy, innocent-looking groundcover that inserts dozens of fine needles into whatever it touches. The sand was full of it, as I’m sure Ali, son of the desert, was well aware. Lessons three and four. I spent the next 15 minutes pulling spines from my feet. Barth called the burr karengia and noted that every native carried tweezers to remove the spines.

It was February, “the month of wind.” The harmattan had started and was blowing hard, kicking up sand and turning the air cloudy. I kept my hat low and my kerchief over my mouth.

After several hours we reached Ali’s village, though that was too grand a name for it, since its inhabitants were so widely scattered that most of his neighbors weren’t visible. Ali’s camp consisted of an open-sided shelter (his house), a small cooking shed made of matting, and a mud-brick room about the size of a one-car garage. Except for the brick building, the camp looked almost exactly the same as depicted in old books and photographs.

Ali’s camp. From left to right: cooking shed, windscreen, domed shelter, mud-brick building

We settled into the mud-brick room. It had a sand floor and a roof of matting laid across a frame of sticks. Ali had built the room in hopes of attracting a teacher, but now it was used mostly by women for sleeping when the winds were bad. He didn’t like being indoors and preferred his shelter. Evidently he assumed that my preferences ran closer to the women’s. He said we would rest here during the day’s hottest hours.

Roof of mud-brick room, contemplated for hours during heat of day

While three of his children watched from the doorway, Ali began the ritual of making tea. He built a small fire on the sand floor. Loose tea went into a battered metal pot that held enough water to fill three or four of the little tea glasses used by Tuaregs. He dumped in a staggering amount of sugar and put the pot on the fire. Periodically he poured tea in a long arc from pot to tiny glass, then returned the tea to the pot for more steeping. Just as I began wondering if we were ever going to drink what he poured, he handed me one of the glasses. The liquefied sugar carried a nice hint of tea.

When the first pot was empty, which didn’t take long, he refilled it with water and sugar, and restarted the process using the same leaves. We drank three pots, which passed the time and jacked up my blood sugar.

Neia, Ali’s wife, and children

Ali wasn’t much for conversation. His wife, Neia, who did sometimes smile, brought in lunch, an aluminum bowl of tasty rice with bits of gristly meat. She handed me a carved wooden spoon. Ali relied on his right hand, scooping up a wad of rice, squishing it into his palm to form a solid oblong, then popping it into his mouth.

Two men and two women came in. Everyone began chatting in Tamasheq. Ali started a batch of fresh tea. One of the men wore a vivid turquoise robe and a flamboyant bright green neck garment with fringe. The long fingernails on his dirty hands were painted red. I naively asked Ali if this place had become a hang-out for his neighbors, but when all six began pulling little knotted bundles of jewelry from beneath their robes, I realized they were here because of me, the ensnared customer. Hucksters and retailers.

After a polite interval I escaped and took a walk. Ali’s shelter was domed, with log supports and a roof of thick matting to blunt the desert sun. On the north side the matting came to the ground. The south side was partly open, with a low roof to cut wind and sand. Inside, things hung from rafters. It felt spacious and pleasant.

South side of Ali’s shelter

Interior

A few hundred yards beyond Ali’s camp I took a photo of a fence made of acacia thorn that enclosed some goats.

A boy, maybe 10 years old, rushed over from somewhere and said, “500 francs for the photo.” I laughed. He insisted. I laughed again. He spotted the pen peeking out of my pocket.

A boy, maybe 10 years old, rushed over from somewhere and said, “500 francs for the photo.” I laughed. He insisted. I laughed again. He spotted the pen peeking out of my pocket.

“Give me your pen [le Bic].”

“Sorry, no, I need it.”

“500 francs for the photo.”

I told him he was amusing. He shrugged and walked off. A huckster’s gotta try.

Back in the mud-brick room, Ali was asleep. A burly dung scarab crawled across the sand floor, leaving a delicate trail. Ali’s bright-eyed daughter Fatima, maybe six or seven years old, stared at me. The sides of her head were shaved, with a spikey mohawk running down the center of her scalp. Barth had seen the same style among Tuareg boys. It gave her the look of a wild child. She pointed at my face, then herself. I didn’t understand until she leaned over and pulled at my glasses. When I jerked backward, she flashed her wild-child grin and ran off.

Ali and his son Mohamed

Tuareg saddle

In late afternoon it was finally time to go. Ali’s son Mohamed saddled the camels—first a blanket folded four times, then a thick leather pad, then the saddle itself. He put a rope under the camel’s belly and over the hump, and pulled the saddle tightly backward to stabilize it. We mounted—by that point I knew how to shift my weight—and we rode into the dunes toward Timbuktu.

Days and Nights in Timbuktu

Mornings in a Muslim town begin before dawn with the muezzins’ first call to prayer. As rousters of slugabeds, muezzins put roosters in the shade, or rather leave them in the dark. To a sleeping Westerner, the amplified chanting seems to start in the middle of the night. If there are several mosques in the vicinity, the chanting overlaps, sometimes in counterpoint, sometimes in dissonance. In Timbuktu my hotel, Sahara Passion, was close to a small mosque but near enough to others that their prayers floated through the darkness into my waking mind.

Small mosque near Sahara Passion

The muezzins eventually wake up the roosters, who, with loud indignation, do their best to reassert dibs on dawn. The muezzins and roosters motivate the goats and donkeys, who add bawling and braying to the morning orchestra.

Soon after the prayers stop and the livestock calms down, the smell of cooking fires begins drifting through town, followed by the rhythmic thuds of women pounding millet. Even in Barth’s day, Timbuktu was known for its delicious flatbread, takola, baked every morning in tall clay ovens shaped like beehives. The bread resembles pita in size and shape but is thicker and chewier, and is usually gritty with a bit of windblown sand. Barth typically ate it for breakfast. So did I, coated with local honey.

Bread oven

A walker in Timbuktu moves between past and present. The main streets are paved and busy with the usual traffic of motorcycles and Land Rovers, but donkeys and camels also plod along. The sand streets of the old medina, built for human and animal pedestrians, are too narrow for cars, though motorcycles occasionally slip-slide through. In many of the sandy side streets, rubble sits alongside stacks of new bricks, reflecting the endless cycle of building and rebuilding with sand and mud.

Brickmaker

Bricks drying

At night I walked 10 or 15 minutes down a wide sand road to get dinner at Amanar, the only restaurant near Sahara Passion. The northwestern edge of the city lacked electricity and the road was pitch dark. I memorized the silhouettes of a few houses so I could find my way back (but still got briefly lost in the ink). Other walkers stayed invisible until their dark outlines suddenly passed. I could smell cooking fires and hear distant singing, drumming, and occasional laughter.

Road to Amanar in daylight

Eventually the dim glow of Amanar appeared, at the frontier of electricity. Its tables sat on a patio surrounded by a low wall. That first night, only one table was occupied, by a young man who turned out to be the waiter. I ordered a cold beer–a small miracle in a desert Muslim town. He brought it and companionably sat down with me, since it was inconceivable that I might want to be alone.

Within minutes a young Tuareg in traditional blue robes emerged from the dark and sat with us. He wondered if I would like to see some Tuareg jewelry, and put two pairs of silver earrings on the table. When I didn’t immediately say no, he pulled out his inventory of rings, bracelets, and pendants.

It was all distinctive, I was a rookie, I overpaid. After he faded into the dark, two Tuaregs replaced him. I saw the game and stopped playing. They left. My dinner appeared and so did two more Tuaregs, who sat down and displayed their wares. I thought of Barth, constantly beset by what he called “hucksters and retailers.” Tuaregs, he noted, were especially persistent.

For several nights this routine repeated itself with minor variations. One night the waiter was sitting with a friend, so I assumed he wouldn’t join me. But when I got up to look at the posted menu, he moved my beer and notebook to their table. There was still plenty of room for the parade of Tuareg retailers.

Flamme de la Paix

Amanar sat across from the Flamme de la Paix, a monument on the site where Tuareg rebels ceremonially burned 3,000 guns in 1996 to signify the end of the Tuareg uprising of 1990-1995. During my visit, the monument offered a handy dark hangout for Tuareg hucksters passing the time while awaiting prey at Amanar.

I never expected to see such a sleepy place in the news. Last November as four Europeans were eating at Amanar, gunmen swooped in and ordered them into a car. A German who resisted was instantly killed. The other three were abducted—the first kidnappings of Westerners in Timbuktu in recent memory. The gunmen were suspected to be from al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), which funds itself partly by kidnapping and ransoming Westerners.

Since the coup in Mali earlier this year, circumstances in Timbuktu have worsened considerably. Two rebel groups took advantage of the political chaos to occupy several northern towns, including Timbuktu, with the avowed goal of forming an independent desert state. Timbuktu is now controlled by a group supported by al-Qaeda that calls itself Ansar Dine (Defenders of the Faith).

Since the time of Ibn Battuta (1352), visitors to Timbuktu have commented on the inhabitants’ sociability and love of dancing, singing, and smoking. But the Ansar Dine are Islamic fundamentalists. They have stopped the singing and the music, and are requiring all women to veil their faces. Tobacco and alcohol have been banned, and places that sold them have been shuttered or destroyed. Amanar is almost certainly among them.

Timbuktu has seen it all before. Many similar restrictions were in place when Barth visited. The town had been captured by Islamic fundamentalists from Hamdallahi, who raided homes to seize tobacco and fined citizens for insufficient piety. The cycles of history.

Eating Local: Locusts and Elephants

All African explorers endured afflictions: sickness, biting insects, vile water, dangerous animals, extreme temperatures, miserable accommodations, hostile people. Throughout it all, they needed to eat. Sometimes food eased their miseries, sometimes worsened them. And of course they often went hungry.

Barth’s and Overweg’s contracts with the British government required them to provide their own food. They ate well during the first part of the journey, supplementing rice and grains with the meat of hares or gazelles chased down by greyhounds or bought from hunters. In Murzuk, 500 miles into the Sahara, the pasha served them coffee and sherbet, and the British vice-consul feted them on roasted lamb and dried sardines, accompanied by rum, wine, and bottled stout.

Ostrich egg among smaller yolks, by Rainer Zenz

The menu soon changed. Deeper into the desert, their stores ran short. The few people they came across who didn’t want to rob or kill them didn’t have any spare food to sell. When they found an ostrich egg, wrote Barth, it “caused us more delight, perhaps, than scientific travelers are strictly justified in deriving from such causes.”

After the austerities of the Sahara, Kano was a culinary high point. The market there offered everything a hungry man craved. Barth relished the street food: “Diminutive morsels of meat, attached to a small stick, were roasting, or rather stewing, in such a way that the fat, trickling down from the richer pieces attached to the top of the stick, basted the lower ones. These dainty bits were sold for a single shell or ‘uri’ each.”

He also enjoyed the market’s roasted locusts, still a valued source of protein in sub-Saharan Africa. Barth called the taste “agreeable.” Many African explorers reviewed the dish. Friedrich Hornemann said roasted locusts had a taste “similar to that of red herrings, but more delicious.” David Livingstone pronounced them “strongly vegetable in taste, the flavor varying with the plants on which they feed. . . . Some are roasted and pounded into meal, which, eaten with a little salt, is palatable. It will keep thus for months. Boiled, they are disagreeable; but when they are roasted I should much prefer locusts to shrimps, though I would avoid both if possible.” Gustav Nachtigal also preferred them roasted. Of the dozen kinds eaten by natives, he was partial to the light-brown ones, though the speckled green-and-whites were also fine.

He also enjoyed the market’s roasted locusts, still a valued source of protein in sub-Saharan Africa. Barth called the taste “agreeable.” Many African explorers reviewed the dish. Friedrich Hornemann said roasted locusts had a taste “similar to that of red herrings, but more delicious.” David Livingstone pronounced them “strongly vegetable in taste, the flavor varying with the plants on which they feed. . . . Some are roasted and pounded into meal, which, eaten with a little salt, is palatable. It will keep thus for months. Boiled, they are disagreeable; but when they are roasted I should much prefer locusts to shrimps, though I would avoid both if possible.” Gustav Nachtigal also preferred them roasted. Of the dozen kinds eaten by natives, he was partial to the light-brown ones, though the speckled green-and-whites were also fine.

Barth ate meat whenever he could get it, domesticated or wild. Sometimes when he stopped in a village, the chief would send him a sheep or a bullock. During his first months in Timbuktu he ate pigeons every day. In some areas guinea fowls were common. On rare occasions he ate antelope and aoudad (Barbary sheep). Barth and Overweg agreed about the tastiest meat in Africa: giraffe. They also liked elephant, though its richness tended to cause havoc in the bowels. When possible, they added vegetables such as squash or beans from legume trees to their diet, and fruit such as papayas and tamarinds. In the desert they enjoyed a refreshing drink called rejire made from dried cheese and dates.

Tamarind tree at right

Guinea corn and millet

But most of the time they lived on grains, especially guinea corn, wheat, sorghum, and millet, prepared in dozens of ways—stewed, mashed, baked, roasted, rolled, fried, pancaked—sometimes mixed with milk or vegetables or bits of meat or cheese. En route to Timbuktu Barth’s typical dinner consisted of millet with vegetable paste made from tree-beans; for breakfast he mixed the cold paste with sour milk. He was fond of fura, bean cakes, and various dishes made from white guinea corn. On the other hand, in Musgu he was unable to choke down a paste made from red sorghum. During one long stretch he lived on boiled mashed groundnuts, which he grew to hate.

Guinea corn

His deepest appreciation went to one simple food: “Milk, during the whole of my journey, formed my greatest luxury; but I would advise any African traveler to be particularly careful with this article, which is capable of destroying a weak stomach entirely; and he would do better to make it a rule always to mix it with a little water, or to have it boiled.”

The milk in Kukawa, however, disgusted him, because the Kanuris added cow’s urine to it, imparting a tang that he found repellent. Kanuris (and some Fulanis) still clean their milk bowls with cow urine, believing that it keeps the milk from going sour for several days. This practice nudged Barth towards camel’s milk, which he came to prefer.

I’ve eaten some things considered weird by American tastes–cow’s stomach, pigs’ ears and testicles, fried grasshoppers and fresh-roasted termites, rattlesnake and blue jay, guinea pig and crocodile–all mainstream fare for Barth and other explorers, who always ate the local food.

I thought of Barth in Lagos as I tried nkwobi, a dish the menu described as “soft cow leg pieces in a secretly spiced sauce, with ugba and topped with fresh utazi leaves.” So many unknowns, so irresistible. But the secret sauce covered a mass so repulsively gristly and gelatinous that I couldn’t eject it from my mouth fast enough. “Cow leg pieces” turned out to mean “hooves.” Even Barth might have hesitated.

El Gatroni

Many explorers in Africa traveled with squads of servants. Lack of funds limited Barth to two, sometimes three. The cast changed often, especially in the first year or so when servants often quit or were fired. But one African stayed with Barth for almost the entire expedition. His name was Muhammed al-Gatruni—that is, Muhammed from Gatrun (also spelled Gatrone, Katrun, and Qatrun), a Saharan village in southern Fezzan, in present-day Libya. Barth called him el Gatroni.

Muhammed al-Gatroni--el Gatroni

This remarkable man spent years assisting Europeans in the exploration of Africa. He served not only Barth but several subsequent travelers who hired him because of Barth’s strong recommendation.

El Gatroni was a Teda, a division of the Tebu people. When Barth hired him in Murzuk in mid-1850, he was 17 or 18, “a thin youth of most unattractive appearance,” wrote the explorer, “but who nevertheless was the most useful attendant I ever had; and, though young, he had roamed about a great deal over the whole eastern half of the desert and shared in many adventures of the most serious kind. He possessed, too, a strong sense of honor, and was perfectly to be relied upon.” Whenever Barth mentions el Gatroni in Travels and Discoveries, it’s always with similar appreciation: “our best and most steady servant,” “upon whose discretion and fidelity I could entirely rely.”

El Gatroni stayed with Barth to the end of the expedition in 1855, except for a hiatus when the explorer entrusted him to take Richardson’s effects and precious journals to Murzuk. When Barth decided to try for Timbuktu, an extremely dangerous journey, el Gatroni agreed to accompany him as chief servant. His salary: one horse, four Spanish dollars a month, and a bonus of fifty Spanish dollars if the expedition succeeded (that is, if Barth lived). His assistance was so valuable that at the end of the journey Barth regretted being unable to double el Gatroni’s bonus.

Henri Duveyrier

Some years later, when Barth was writing Travels and Discoveries in London, he met a French teenager named Henri Duveyrier who dreamed of exploring the Sahara. Barth advised him to learn Arabic and, if he ever went to Central Africa, to hire el Gatroni. Duveyrier took this advice. El Gatroni accompanied the Frenchman on some of the travels that made him famous.

In Germany, Barth’s example inspired Karl Moritz von Beurmann to undertake an expedition into Bornu in the early 1860s. Barth again recommended el Gatroni, who guided von Beurmann to Kukawa. The explorer proceeded to Wadai, where he was murdered. Barth also inspired his countryman Friedrich Gerhard Rohlfs, who followed Barth and von Beurmann to Bornu in the mid-1860s. Rohlfs’s guide, on Barth’s suggestion, was el Gatroni.

Friedrich Gerhard Rohlfs

A few years later Rohlfs arranged for el Gatroni to lead Gustav Nachtigal on part of that explorer’s remarkable five-year odyssey through Central Africa. Nachtigal, who called Barth “my constant example,” knew all about el Gatroni and described his first meeting with him in 1869 as the famous guide stuffed pack saddles for their upcoming trip:

“I looked with respectful awe upon his round, black face, with its innumerable wrinkles, his small snub nose with wide nostrils, his toothless mouth, the sparse black and white hairs of his beard, his large ears and his faithful eyes.

“As I had frequent occasion to observe in the years which followed, old Muhammad was not a man of many words. A quiet friendly old man, he was by no means indifferent to the joys of life; he seldom, however, allowed the equanimity which was the result of his temperament and his rich experiences to be disturbed.”

Gustav Nachtigal

Though Nachtigal often called el Gatroni old, the guide was only a year or so senior to the 35-year-old Nachtigal, but his face was carved with a life of rough travels.

When Nachtigal wanted to explore Tibesti, in what is now northern Chad, el Gatroni strongly advised against such a dangerous trip and didn’t want to go. Nachtigal asked him to recommend someone else as a guide. “The worthy man, however, rejected this proposal with some indignation,” wrote Nachtigal. “‘I have promised your friends in Tripoli,’ he added, ‘to bring you safe and sound to Bornu, just as I also guided thither your brothers, ‘Abd el-Kerim (Barth) and Mustafa Bey (Rohlfs). With God’s help we shall achieve this purpose together. Until then I shall not leave you, and should misfortune befall you among the treacherous [Tebu], I want to share it with you.’”

The expertise and steadfastness of men such as el Gatroni helped make possible the exploration of Africa by Europeans.

Explorer in Training: Part 2

Barth spent most of his tour around the Mediterranean in North Africa and the Middle East. He first touched Africa at Tangiers, then proceeded east towards the Nile and on to the Levant. “I spent nearly my whole time with the Arabs,” he wrote, “and familiarized myself with that state of human society where the camel is man’s daily companion, and the culture of the date-tree his chief occupation.”

Date palm tree, by Balaram Mahalder

The trip was invaluable training for the great journey to come. He tested himself by traveling through dozens of cultures, many of them Islamic. He learned how to cope with fever, illness, and gunshot wounds–in Egypt he survived an attack by Bedouin thieves who shot him in both legs and left him unconscious. He became skilled at traveling leanly and alone for long periods. He perfected his Arabic and picked up several other languages, including Turkish, which would one day come in handy at a crucial moment as he attempted to enter Timbuktu disguised as a Syrian sherif. He trained himself to recognize links between a region’s history, geography, languages, and cultures, links he would later find in central Africa. The trip exhilarated him. He was gone for nearly three years.

Spending so much time alone in the desert reinforced his misfit tendencies. “He had become the very model of the imperious, the closed-off, and the ascetic,” remembered Gustav von Schubert, Barth’s brother-in-law, intimate friend, and biographer. Shortly before Barth returned, von Schubert had started courting the explorer’s beloved younger sister, Mathilde. “Later we became close friends,” wrote von Schubert, “but it took a long time before I was able to thaw the ice around his heart and experience the depths of his character. In his first letter to me, he wrote, ‘If you make my sister unhappy, I will shoot you dead,’ which was clear enough.”

Barth wasted no time pursuing his three main goals: to write a scholarly multi-volume account of his journey, to secure an academic position, and to get married. Things looked promising, at first. He found a publisher. He got a part-time job in the archeology department at the University of Berlin. He beseiged a prospective bride.

Nothing worked out. The first volume of his book, Wanderings Along the Shores of the Mediterranean, was praised for its meticulous scholarship but slammed for its boring style and presentation. The public declined to buy it, so the publisher cancelled the second volume. Nevertheless, the book established Barth among Berlin’s influential academics and scientists as a formidable scholar who was also fearless and tireless.

At the university, he lectured on soil composition. His droning recitation of data stupefied his students, who stopped coming. The class was dropped. Barth must have been equally scintillating as a suitor—his prospective bride dropped him too.

By autumn of 1849, Barth felt pummeled by failure. Yet the trip around the Mediterranean had confirmed his passions: deep scholarship and rigorous travel. If only there was some way to combine them into a living. He began daydreaming about a long journey into Asia. He was twenty-eight.

James Richardson

While Barth was licking his wounds, an English abolitionist named James Richardson finally persuaded the British Foreign Office to fund a journey into the unknown lands of central Africa called the Sudan, south of the Sahara. The mission’s main purpose would be to sign treaties with the region’s chiefs and to scout potential markets for British commerce, but the Foreign Office required Richardson to take along a scientist to gather infomation about these mysterious peoples and places.

At the time, Germany was producing the best-trained scientists in the world, so that’s where Richardson turned for help. Two of Germany’s most eminent scientists, Carl Ritter and Alexander von Humboldt, conferred and immediately agreed on a candidate: their former student Heinrich Barth, recently returned from his three-year journey through North Africa and the Middle East.

Carl Ritter

So in early October 1849, Ritter called Barth to his office and asked him a question that changed everything: would he be interested in departing almost immediately with a British expedition into the Sudan?

Explorer in Training: Part 1

The first Europeans to reach the kingdom of Bornu on Lake Chad were the British explorers Walter Oudney, Hugh Clapperton, and Dixon Denham. They left England in 1821, the same year Heinrich Barth was born in Hamburg, Germany. In one of history’s coincidences, Barth would be the next European to see Bornu, 30 years later.

At the palace of the Sheikh of Bornu, from a sketch by Dixon Denham

Barth’s father, Johann, was the son of German peasants who died when Johann was a boy. A relative in Hamburg took in the orphan. Though uneducated, Johann had the energy and ambition to work his way into the city’s middle class while building a thriving business as a trader in the cities along Germany’s northern coast. His success allowed him to marry well: Barth’s mother, Charlotte, came from a respected Hamburg family. The couple were strict Lutherans who raised their four children—Heinrich was the third—according to strict standards.

Richard Francis Burton

Some explorers, such as Richard Francis Burton and Samuel Baker, spent large parts of their boyhoods hunting, roaming the woods, and having open-air adventures that, in retrospect, were preludes to future exploits.

By contrast, the young Barth gave no sign that he would someday be a great explorer. Well, one sign: like Burton, Baker, and most other explorers, he was a misfit. Dweebish and physically weak, he devoted himself to art, languages, and book-collecting. His fellow students found him amusingly peculiar. He had few friends.

A childhood classmate later recalled that Barth “studied subjects that were not even part of the curriculum. People said that he was teaching himself Arabic, which to us brainless schoolboys certainly seemed the pinnacle of insanity.” Barth taught himself not only Arabic but English, which he could read and speak fluently by age thirteen, a handy skill in years to come. His other extracurricular missions included reading the histories, geographies, and scientific works of the classical Greeks and Romans, in the original languages.

In his mid-teens he undertook physical renovations. During recess, while the other boys played, he did gymnastics and arm exercises. To toughen himself he took cold baths, even in winter. By the time he entered the University of Berlin in 1839, he was a robust young man well over six feet tall.

There’s no evidence that Barth thought of these mental and physical regimens as preparations for life as an explorer. He was probably modeling himself after his beloved Greeks and their ideal of physical and intellectual excellence. He went to college expecting to earn an advanced degree and settle into a comfortable, sedentary career as a university professor.

Wanderlust and circumstances demolished those plans. During his second semester at the university, restlessness overcame him. He told his father he wanted to drop out and make an academic excursion to Italy, funded by Dad. Most parents, presented with this plan by a 19-year-old, would smell a boondoggle. Johann, however, knew his somber son had no interest in la dolce vita. He funded the trip.

Barth prepared with his usual diligence, first by learning Italian. He spent nearly a year traveling alone to classical sites throughout Italy, taking copious notes on everything he saw. “I am working terribly hard,” he wrote home from Rome in November 1840. “I go everywhere on foot. It has become no problem for me to walk around for nine hours without eating anything apart from a few chestnuts or some grapes.” The trip sparked a lifelong urge to see new places.

In June 1844 he received a Ph.D. for his dissertation on trade relations in ancient Corinth, a busy port like Hamburg. He moved back into the family home there and spent six months studying ten hours per day, in hopes of earning a university appointment. Nothing came of it.

Disappointed and itchy to escape his desk, he asked his father to fund another research trip, far more ambitious (and expensive) than the one to Italy. He wanted to circumambulate the Mediterranean Sea, visiting the three continents it touched and the cultures it influenced. Writing a scholarly book about his trip, he told Johann, would help him secure a university position. Johann again opened his wallet. The trip altered the course of Barth’s life.