The Boston Globe has named A Labyrinth of Kingdoms one of 2012’s eleven best books of nonfiction, putting it in some distinguished company. I’m honored.

Nearing the End of the Journey

It’s been almost a year since I started this blog about Heinrich Barth and his travels. My book about his great expedition is now three months old. I think it’s time for the caravan to move on. I’ll continue to post if something relevant occurs to me, but will no longer maintain a regular schedule. Thank you for reading the blog. If you read the book, please let me (and Amazon!) know what you think about it.

It’s been almost a year since I started this blog about Heinrich Barth and his travels. My book about his great expedition is now three months old. I think it’s time for the caravan to move on. I’ll continue to post if something relevant occurs to me, but will no longer maintain a regular schedule. Thank you for reading the blog. If you read the book, please let me (and Amazon!) know what you think about it.

Meanwhile I’m deep into the research for a book about another adventurer, an American this time. New journeys just ahead.

Why Timbuktu Will Overcome Its Latest Fundamentalist Conquerors

Caravan routes

Many of today’s headlines about Islamic north-central Africa would look familiar to the explorer and scientist Heinrich Barth, who traveled 10,000 miles there for the British from 1850 to 1855. The caravan routes ridden by Barth are now roads, but the arid territories they cross are still a nexus of distinctive cultures that have mixed and chafed for centuries. Old frictions still flare up between Muslims and non-Muslims, black and brown, fundamentalists and moderates, central governments and local chiefs.

As in Barth’s day, bandits and fanatics keep the region in turmoil. The group Boko Haram (“Western education is forbidden”) has killed hundreds of people in places Barth visited in northeastern Nigeria, bombing government offices, schools, and Christian churches. The group’s violent quest to “purify” Islam is just the most recent of similar jihads reported by Barth. Other groups, now as then, use religion as a veneer to justify thuggery. The terrorists of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), for instance, seem motivated more by money than by Mohammed, kidnapping Western travelers whom they murder or ransom — behavior that Barth witnessed and survived.

For Barth, Boko Haram and AQIM would be familiar manifestations with historical precedents. So would the distress of today’s moderate Muslims who want to reclaim their religion’s traditions of tolerance and learning from gangsters and extremists.

Some current events are almost historical reenactments. In March of this year, after the Malian military staged a coup, several rebel groups took advantage of the political chaos to occupy Mali’s northern half, including the ancient desert towns of Timbuktu and Gao. The group that now controls Timbuktu is associated with AQIM and calls itself Ansar Dine (“Defenders of the Faith”). Like Boko Haram, the Ansar Dine are fundamentalists intent on imposing their version of a purer Islam. If history is a guide, they would have better luck pushing a camel through the eye of a needle.

Ibn Battuta

Since the time of Ibn Battuta (1352), visitors to Timbuktu have been impressed by the town’s scholars and amiable inhabitants, known for their love of singing, dancing, and smoking. The Ansar Dine have stopped the singing and the music, and are requiring women to veil their faces, atypical in Timbuktu. Tobacco and alcohol have been banned, places that sold them have been shuttered or destroyed, and possession of a cigarette brings a beating. Women have been whipped for immodest behavior such as walking alone or riding in a car with men. In a town near Timbuktu, an unmarried couple was stoned to death.

Ignorance, that frequent collaborator with fanaticism, has led the Ansar Dine to destroy at least half a dozen of Timbuktu’s historic tombs and monuments, including part of the fourteenth-century Djingereber mosque, on grounds of idolatry. Scholars fear that Timbuktu’s invaluable manuscript libraries might be looted, perhaps for the purpose of selling these volumes of old Islamic erudition to fund new Islamic intolerance.

Ignorance, that frequent collaborator with fanaticism, has led the Ansar Dine to destroy at least half a dozen of Timbuktu’s historic tombs and monuments, including part of the fourteenth-century Djingereber mosque, on grounds of idolatry. Scholars fear that Timbuktu’s invaluable manuscript libraries might be looted, perhaps for the purpose of selling these volumes of old Islamic erudition to fund new Islamic intolerance.

Timbuktu has weathered it all before. Similar restrictions were in place when Barth spent seven months there under house arrest in 1853-54. Muslim jihadists from the newly-declared kingdom of Hamdallahi (“Praise to God”) had conquered Timbuktu in 1826. They attempted to impose harsh reforms: no tobacco, mandatory attendance at mosque, segregation of men and women. The sociable smoking dancers of Timbuktu considered these dictates preposterous. By the time of Barth’s visit, the fundamentalists had despaired of separating Timbuktu’s men and women, but Barth recounts how they raided homes to seize tobacco and levied fines for insufficient piety.

Timbuktu has weathered it all before. Similar restrictions were in place when Barth spent seven months there under house arrest in 1853-54. Muslim jihadists from the newly-declared kingdom of Hamdallahi (“Praise to God”) had conquered Timbuktu in 1826. They attempted to impose harsh reforms: no tobacco, mandatory attendance at mosque, segregation of men and women. The sociable smoking dancers of Timbuktu considered these dictates preposterous. By the time of Barth’s visit, the fundamentalists had despaired of separating Timbuktu’s men and women, but Barth recounts how they raided homes to seize tobacco and levied fines for insufficient piety.

Today’s residents of Timbuktu, Gao, and nearby desert towns have begun staging protests and forming militias to resist Ansar Dine’s severe version of Islam. It seems likely that long after Ansar Dine has vanished into history like Hamdallahi, Timbuktu and its people will still be singing and smoking.

Barth blamed much of the region’s misery on its greedy, corrupt leaders, who devastated the region with constant warfare and slave raids. “Even the best of these mighty men,” he wrote, “cares more for the silver ornaments of his numerous wives than for the welfare of his people.” Today’s Nigerians ask why their government can’t protect them from Boko Haram, and why a country with some of the world’s richest oil deposits must import most of its gas and can’t light its largest cities. Greed and corruption, wrote Barth, inspired violent purifying jihads that imposed their own repressions. These criticisms still sound fresh.

As in Barth’s day, most Westerners know little about Islam or Africa, and distort them into simple monoliths. Barth carried some of his era’s assumptions, but he was willing to go where the evidence took him. He found ignorance and savagery in Africa — the prevailing European view of the continent — but also scholars and sophisticated systems of commerce and government.

He likewise challenged the dominant European view of Islam as an evil dangerous opponent of Christian civilization, which still sounds familiar. Consider the recent Republican presidential primary, in which nearly every candidate expressed alarm about the nonexistent threat of Sharia law in the United States. Members of Congress are on record about “terrorist babies” and “stealth jihadis.” American towns have voted to ban mosques, and corporations tremble when fringe groups accuse them of being pro-Muslim.

Barth called Islam a great religion — not a popular view, then as now — but added that in some places it had been hijacked by brigands or fanatics who used it as an excuse to pillage or to subjugate. He pointed out that Islam wasn’t much different in these ways from Christianity, another great religion sometimes hijacked by the greedy or the self-righteous. All of this remains in the headlines.

Unlike most pundits about the continent, then as now, Barth formed his views from close observation of African reality. His news and perspective remain pertinent. As a scientist he believed that knowledge can dissolve ignorance and misunderstanding. Perhaps it still can, given the chance.

*This originally appeared on the History News Network on August 22, 2012.

Images: Some Expedition Documents

A few of the dozens of pages devoted to merchandise taken by the expedition. First, arms and ammunition:

Supplies:

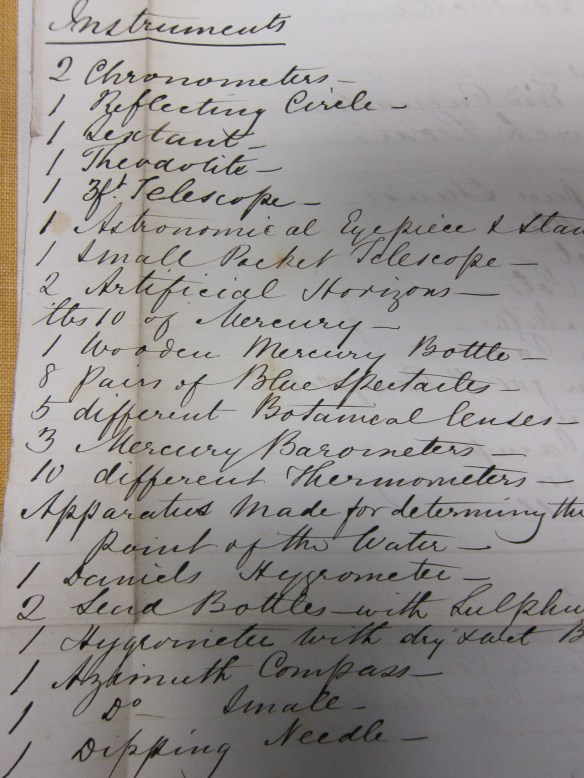

Instruments:

Letter of transit in Arabic, carried by Barth, given to him by the Sultan of Bagirmi, who held him prisoner for months:

Barth’s English translation of the letter of transit, written on opposite side:

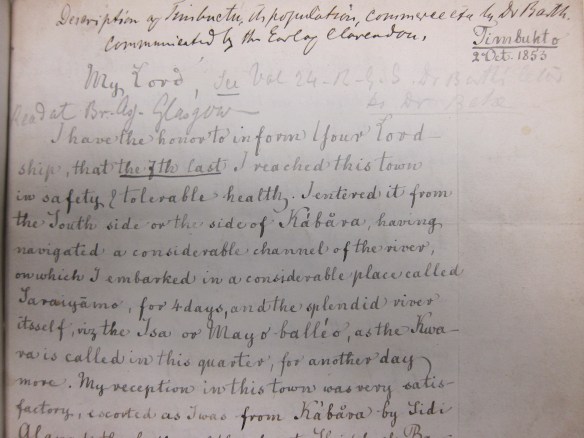

Barth’s letter to the British Foreign Office announcing his safe arrival in Timbuktu:

Barth’s IOU to some Ghadamsi merchants, entailed on his way home:

August Petermann, Cartographer of Exploration

Heinrich Barth’s invitation to join the British expedition can be traced back to a German cartographer named August Petermann. Petermann was working at the London Observatory when he heard about James Richardson’s proposed African expedition and its need for a scientist. Petermann told Chevalier Bunsen, the Prussian ambassador to the Court of St. James’s, who approached Richardson and offered to find him the best available German scientist. Richardson was delighted, since Germany’s scientists were considered the finest in Europe. Carl Ritter and Alexander von Humboldt, eminences at the University of Berlin, recommended Barth.

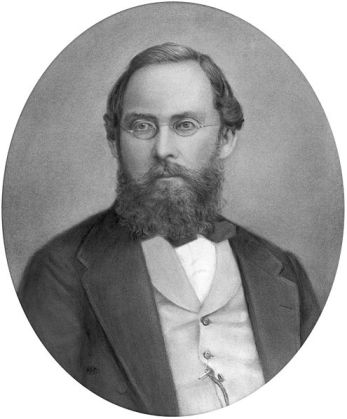

August Petermann

From the start, Petermann took a keen, almost proprietary, interest in the expedition. He became an important long-distance affiliate and cheerleader. He lobbied the British Foreign Office to send more funds and helped to arrange for another German scientist, Eduard Vogel, to join the expedition. When Barth sent rough maps and measurements of the mission’s routes back to Britain, the Foreign Office hired Petermann to turn them into works of cartography.

All this was fine, but in his over-enthusiasm Petermann also sent his maps to German publications, along with information from Barth’s dispatches. This did not sit well with some people at the FO and the Royal Geographical Society, and fed the resentment against Germany in some British quarters that I described in an earlier post.

All this was fine, but in his over-enthusiasm Petermann also sent his maps to German publications, along with information from Barth’s dispatches. This did not sit well with some people at the FO and the Royal Geographical Society, and fed the resentment against Germany in some British quarters that I described in an earlier post.

“Of course it is Mr. Petermann’s object,” wrote the FO under-secretary, “to make himself, for his own profit, and also for his own glory, the historiographer of all the discoveries of Barth and Overweg: but that is not our object, or intention . . . Drs. Barth and Overweg were members of Richardson’s expedition, paid by us, and traveling at our expense,” he continued, and any public announcements about the expedition should come from the Royal Geographical Society, “which properly speaking is our natural medium of partial geographical communications.”

Petermann and Chevalier Bunsen, he added, seemed to consider the British “the mere paymasters of the expedition, while the fruits belong to Germany. This is a mistake.”

The secretary of the RGS expressed his irritation more crudely, writing about the expedition in the society’s journal, “In connection with Lake Chad and other African names, it may be observed that the Germans are adopting various ways of spelling them, because they find it difficult to say ‘cheese.’”

This was too much for Petermann. He responded with a nine-page open letter that called the RGS report “scurrilous and offensive.”

When Barth returned to England, he stepped into this stew. Under questioning from the RGS and the FO, he agreed that Petermann sometimes published information about the mission too hastily, but added that he was motivated by his scientific eagerness to share information, not by German nationalism.

Barth admired Petermann’s passion for exploration and his exquisite skills as a cartographer. (Petermann’s numerous maps are one of the glories of Barth’s book. See examples here, here, and here.) Petermann was also indirectly responsible for the book’s wonderful illustrations. He recommended that Barth hire the German artist J. M. Bernatz, who turned Barth’s sketches into the book’s many finished drawings.

Barth’s entry into Timbuktu

But the cartographer sometimes exasperated the explorer. Barth once wrote, “I believe Petermann has really convinced himself that the African expedition was his work, not mine, and that Providence only brought me safely through all those unspeakable dangers thanks to his ideas and his leadership abilities. . . . Despite his great and justifiably rewarded abilities, Petermann is a real loudmouth.”

Petermann returned to Germany in the mid-1850s and continued to publish extraordinary maps based on discoveries by explorers all over the globe. In appreciation, explorers named geographic features on several continents after him. His devotion to exploration and meticulous cartography is his enduring legacy.

His personal life, however, was evidently unhappy, and he may have been a manic-depressive. In October of 1878, aged 56, he killed himself with a pistol.

—–

In other news, A Labyrinth of Kingdoms was last week’s “Book of the Week” in The Times of London, which gave it an enthusiastic review (restricted access): A Labyrinth of Kingdoms by Steve Kemper.

Labyrinth: Reviews & Interviews

Some recent reviews and interviews about the book:

Boston Globe review.

Shelf Awareness review.

Bibliobuffet review.

Expedition News review.

Wall Street Journal review and my response.

Christian Science Monitor interview.

Pen on Fire audio interview.

New Books Network audio interview.

History in the Margins interview.

Conversation Crossroad audio interview.

One-on-One interview.

Biblioklept interview.

The Hill of the Christians

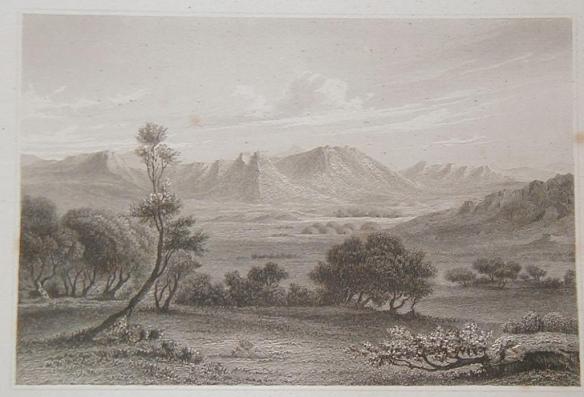

One of the most fascinating and perilous segments of Barth’s journey occurred in the district of Aïr in the Sahara, in present-day Niger. About 300 miles long and 200 miles wide, Aïr consists of steep disconnected massifs and volcanic cones, some rising more than 6,000 feet from the desert floor. Barth called it “the Switzerland of the desert.” Until he described it, Europeans were unaware that the Sahara contained such landscapes. Before Barth’s party entered the region, no European had ever set foot there. European visitors would be extremely rare for many decades afterwards.

The landscape of Aïr. From Travels and Discoveries.

In Barth’s day, Aïr was an isolated redoubt occupied by gangs of Tuareg brigands who had never been subdued by an outside power. This remained true, off and on, for next 150 years. I had hoped to visit Aïr while researching my book, but the district was off-limits to travelers because Tuareg rebels had a base there.

At the time of Barth’s journey, the capital of Aïr was Tintellust, deep in the region’s heart. Barth’s group reached there soon after being plundered and nearly murdered by Tuaregs in Aïr. The Europeans expected Tintellust to be a city, but it turned out to be a village of 250 dwellings shaded by trees in a pleasant mountain valley. The explorers weren’t too disappointed, because for the first time in weeks they felt safe. Tintellust was the home of Sultan Annur, leader of the Kel Owis, a Tuareg tribe. For a large sum, Annur agreed to protect the expedition.

Annur told the Christians to camp at a spot 800 yards from the village on some sand hills. The location offered sweeping views of the valley and the mountains. Barth predicted that the place would henceforth be called the “English Hill” or the “Hill of the Christians.”

Tintellust

Francis Rennell Rodd, a British explorer, traveled in Aïr in the 1920s and wrote a wonderful book about it called People of the Veil. Rodd found Aïr and its Tuareg inhabitants exactly as Barth had described them 75 years earlier. I especially like Rodd’s description of male Tuaregs: “The men never grow fat: they are hard and fit and dry like the nerve of a bow, or a spring in tension. Of all their characteristics the one I have most vividly in mind is their grace of carriage. The men are born to walk and move as kings, they stride along swiftly and easily, like Princes of the Earth, fearing no man, cringing before none, and consciously superior to other people.” Their belligerence and opportunism, noted Rodd, hadn’t changed either, as expressed in one of their sayings: “Kiss the hand you cannot cut off.”

Rodd wanted to visit Tintellust to look for traces of Barth, whom he called “perhaps the greatest traveler there has ever been in Africa.” Tintellust wasn’t on any map, but Rodd’s guide knew the village and took him there. As they reached the outskirts, the guide pointed out a place called “the House of the Christians.” When Rodd asked why, the guide said that in the olden days three white Christians who weren’t French had come to Tintellust—not as conquerors, like the French, but as friends of Chief Annur—so the thatch huts where they camped had never been inhabited or pulled down. All that remained of the camp, noted Rodd, were “the traces of two straw huts and a shelter, a wooden water trough, and some broken pots.”

In 2005 Julia Winckler, a British photographer and teacher fascinated by Barth, traveled to Tintellust. She too was shown Barth’s old encampment. She documented her visit to Tintellust (and Agadez) with photographs and videos: www.retracingheinrichbarth.co.uk. In Tintellust, according to Winckler, a story persists that Barth buried treasure nearby, and the villagers occasionally still dig for it. Barth would be amused–by the time he and his ragged group reached Tintellust, they had been pillaged several times and had no surplus to bury.

Shades of Black

As I noted in an earlier post, Africans often considered European explorers ugly, strange, or pitiable because of their white skin. But African attitudes about skin color were not simply black or white. Things were much more complicated than that, and still are.

Perceptions about skin color among Africans go back at least 2,500 years, when lighter-skinned Egyptians reviled darker-skinned Nubians as uncultured savages. Gradations of skin color became part of cultural and racial identity, and remain so. Northern Africans such as Arabs, Berbers, and Tuaregs often have dark skin but call themselves white to contrast themselves with southern Africans. They sometimes assume that their relative lightness makes them racially superior to black Africans, just as Europeans assumed that whiter meant better.

Perceptions about skin color among Africans go back at least 2,500 years, when lighter-skinned Egyptians reviled darker-skinned Nubians as uncultured savages. Gradations of skin color became part of cultural and racial identity, and remain so. Northern Africans such as Arabs, Berbers, and Tuaregs often have dark skin but call themselves white to contrast themselves with southern Africans. They sometimes assume that their relative lightness makes them racially superior to black Africans, just as Europeans assumed that whiter meant better.

Northern Africans, past and present, also feel a sense of superiority because they are Muslims. Northern peoples became the first African converts to Islam as the religion swept across the region, but for centuries the regions below the Sahel remained unconverted. The Qur’an forbade the enslavement of Muslims, but the black Africans who lived to the south were pagans and hence legitimate targets of Muslim slave-raids. This relationship reinforced racial attitudes.

Yet some black Africans from the Sahel made their own racial distinctions and didn’t consider themselves truly black, and still don’t, perhaps a holdover from their longer tradition of Islam compared to tribes farther south. My guide in northern Nigeria, for instance, was a Fulani who remarked that the Kanuris of eastern Nigeria, in contrast to Fulanis and Hausas, were truly black. My other guide in Nigeria, also a Fulani, shaved this distinction even finer. Describing a subgroup of nomadic Fulanis called the Bororos (or Wodaabes) from Gambia and Senegal, he told me, as he rubbed his skin, “They’re really black. We are whiter.”

Yet some black Africans from the Sahel made their own racial distinctions and didn’t consider themselves truly black, and still don’t, perhaps a holdover from their longer tradition of Islam compared to tribes farther south. My guide in northern Nigeria, for instance, was a Fulani who remarked that the Kanuris of eastern Nigeria, in contrast to Fulanis and Hausas, were truly black. My other guide in Nigeria, also a Fulani, shaved this distinction even finer. Describing a subgroup of nomadic Fulanis called the Bororos (or Wodaabes) from Gambia and Senegal, he told me, as he rubbed his skin, “They’re really black. We are whiter.”

Yet in the 1820s explorer Dixon Denham noted that in Bornu, home of the Kanuris, the copper-colored Shuwa women were looked down upon as too white: “black, and black only,” wrote Denham, “being considered by them as desirable.” Such are the absurdities of cultural attitudes based on skin color.

One stark contemporary example of how African attitudes about race still operate is found in the Janjaweed, the murderous raiders in southern Sudan. They have black skin but are descended from Islamic Arab tribes, so their war cry as they attack black tribes (now Christian rather than pagan) is “Kill the slaves!” The Janjaweed’s tactics resemble those used by the Kanuris of Bornu during slave raids, and described by Barth —kill, rape, terrorize, and leave nothing behind for survivors except smoking rubble.

One stark contemporary example of how African attitudes about race still operate is found in the Janjaweed, the murderous raiders in southern Sudan. They have black skin but are descended from Islamic Arab tribes, so their war cry as they attack black tribes (now Christian rather than pagan) is “Kill the slaves!” The Janjaweed’s tactics resemble those used by the Kanuris of Bornu during slave raids, and described by Barth —kill, rape, terrorize, and leave nothing behind for survivors except smoking rubble.

Tim Jeal, Horror, and Rose-Tinted Spectacles

Tim Jeal is the current dean of writers about African exploration, so I was pleased to see his name atop a recent review of A Labyrinth of Kingdoms in the Wall Street Journal. But halfway through it, pleasure turned to dismay. Jeal so badly misrepresents the book, so consistently, that I didn’t recognize it from his descriptions. Maybe Jeal is right and I don’t understand what I’ve written as well as he does. You decide:

Tim Jeal is the current dean of writers about African exploration, so I was pleased to see his name atop a recent review of A Labyrinth of Kingdoms in the Wall Street Journal. But halfway through it, pleasure turned to dismay. Jeal so badly misrepresents the book, so consistently, that I didn’t recognize it from his descriptions. Maybe Jeal is right and I don’t understand what I’ve written as well as he does. You decide:

“Whenever the adult Barth is sympathetic toward Africans, Mr. Kemper approves,” writes Jeal, “but he greets any momentary lapse with horror.” Until the rest of the review made Jeal’s agenda clear, this baffled me. Since Barth constantly complains in the book about Africans who threaten, cheat, rob, and detain him, I must have written a good deal of it in a state of horror, which came as a surprise to me.

Next Jeal says that I depict Europeans “as less moral than Africans.” This empathy for Africans, he adds, “can lead Mr. Kemper to view the African pre-colonial scene through rose-tinted spectacles.” To clinch the charge that I am a naïve liberal, Jeal adds that I emphasize the cultural benefits of Islam and downplay the violence of Islamic jihads.

These accusations also surprised me. In the book I remember writing, Islamic violence and jihad are pervasive. Barth ran into these brutalities everywhere, and constantly lamented and condemned them. I thought I had included all this in the story, but my constant horror, viewed through rose-tinted spectacles, may be clouding my memory.

These accusations also surprised me. In the book I remember writing, Islamic violence and jihad are pervasive. Barth ran into these brutalities everywhere, and constantly lamented and condemned them. I thought I had included all this in the story, but my constant horror, viewed through rose-tinted spectacles, may be clouding my memory.

After complaining that I downplay Muslim violence, Jeal goes on to note that I describe “the butchery of unresisting pagans by African Muslims.” Unfortunately, he continues, “Mr. Kemper often reduces the impact by pointing out, for instance, that European history is littered with massacres and savage punishments.”

This is doubly confusing. If I tend to ignore Muslim violence, how did that butchery sneak in? Second, how does mentioning European atrocities in any way diminish African ones? I hadn’t realized it was a contest. Nor do I understand how holding the mirror up to European assumptions about African barbarity is an apologia for African violence. Barth makes clear, as does my book, that he saw terrible crimes against humanity in Africa, most of it committed by Muslims. Why would Jeal pretend otherwise? Watch closely:

“Yet despite recording such facts, Mr. Kemper expresses simple nostalgia for the lost ‘labyrinth of kingdoms,’ lamenting that Barth ‘was among the last Europeans to witness them before the onslaught of colonialism.’ . . . Mr. Kemper’s regret for their passing seems to owe more to political correctness than to analysis.”

Perhaps someone can help me follow Jeal’s logic: though I record atrocities committed by these Muslim kingdoms, which Jeal earlier accused me of downplaying, I am actually nostalgic for them because of—political correctness? The twisting ingenuity of the argument gives me a headache. I thought my point was historic, not nostalgic. Barth recorded places, cultures, social systems, etc. that would soon disappear. That is what gives his work such value.

Perhaps someone can help me follow Jeal’s logic: though I record atrocities committed by these Muslim kingdoms, which Jeal earlier accused me of downplaying, I am actually nostalgic for them because of—political correctness? The twisting ingenuity of the argument gives me a headache. I thought my point was historic, not nostalgic. Barth recorded places, cultures, social systems, etc. that would soon disappear. That is what gives his work such value.

This brings me to a passage that is almost admirable of its kind:

“The kingdoms had been great centers of Muslim learning and sophisticated trading centers over the centuries, but Barth saw them in terminal decline, bringing misery to many thousands. In Barth’s time, Bornu was, Mr. Kemper concedes, ‘a kingdom in decay, rotted by sloth, waste, avarice and devotion to pleasure.’ In a revealing buried note, he lets slip that the murderous ‘Janjaweed’s tactics [in modern Darfur] resembled the vizier’s of Bornu during a razzia—shoot, kill, rape, loot, and then burn everything to debilitate survivors.’”

Most of the book’s action occurs in kingdoms declining because of sloth, greed, and corruption. That’s one of Barth’s themes and is a strong theme in my book. If this is something that I “concede,” then I spend 300 pages conceding it, evidently while downplaying it in a state of horror despite my rose-tinted spectacles. I also must bow in amazement at the telltale revelation Jeal disinters from that “buried note.” Jeal’s fracking of my subconscious has freed me from the delusion that I put the Janjaweed into the endnotes simply because the contemporary reference didn’t fit into the historical narrative.

In keeping with his determination to paint me as a soft-headed American leftist, Jeal goes on to suggest that I minimize British praise for Barth while promoting a conspiracy theory about anti-British feeling against him. “There was no British anti-Barth plot,” states the Briton Jeal.

In keeping with his determination to paint me as a soft-headed American leftist, Jeal goes on to suggest that I minimize British praise for Barth while promoting a conspiracy theory about anti-British feeling against him. “There was no British anti-Barth plot,” states the Briton Jeal.

Again, this surprised me. I could have sworn that I described how some factions of British society showered Barth with praise, gratitude, and medals. But I also remember describing other Britons who accused him of mismanagement, overspending, slave-dealing, promoting Germany’s commercial interests over Britain’s, denying scientific information to Britain’s scholars in favor of Germany’s, and slurring the honor of a British soldier who accompanied him across the Sahara. All of these charges and insinuations are in the archival record, all are included in the book, all are airily dismissed by Jeal. I don’t remember calling this cluster a plot, but do remember thinking that, taken together, these reactions do indicate some anti-Barth and anti-German bias.

Tim Jeal

I could go on but it would just be more of the same. Jeal does make one accurate statement—that Barth “is neglected because he made no startling geographical discoveries and because discovery rather than scholarship (unless on the Darwinian scale) is what confers lasting status upon travelers.” I make the same point but go on to suggest that Barth deserves to be better known because he returned from Africa with a tremendous treasure of knowledge that has had more enduring value than the headline discoveries of famous explorers. On this point I do concede, as Jeal would say, that my view may come from spectacles tinted rose.

Weird White Men

European explorers went to Africa certain that they carried the banner of civilization and were superior to the natives, whose skin, after all, was dark, and whose fashions and physiognomies often didn’t conform to European models. To some explorers, and to many Europeans who came later, white was right and dark was ugly, barbaric, pitiable.

Africans had a different point of view. The early European explorers often found the tables turned—they were the ones pitied as ugly and barbaric. They were infidels with white skin–unenlightened, unsightly, pathetic. Africans stared at them as if they were circus freaks, sometimes with fright, sometimes with derisive laughter. At first this inversion shocked and sometimes offended the explorers, but most of them soon found it amusing.

Mungo Park

Mungo Park, for instance, was required to display his pale skin several times during his travels through the Gambia, usually for inquisitive women. One group of them asked for visual proof of his circumcision.

Dixon Denham and Hugh Clapperton, who preceded Barth to Bornu in the 1820s, also attracted many inquisitive women, who investigated these white oddities by rubbing their unappealing pasty skin and touching their weirdly-textured hair. “Again,” wrote Denham, “my excessive whiteness became a cause of both pity and astonishment, if not disgust; a crowd followed me through the market, others fled at my approach; some of the women oversetting their merchandize, by their over anxiety to get out of my way. . . . One little girl was in such agonies of tears and fright, at the sight of me, that nothing could console her, not even a string of beads which I offered her—nor would she put out her hand to take them.”

One evening as Denham passed three women in the street, they stopped to question him about why he was there. They also asked, “Is it true that you have no khadems, female slaves? No one to shampoo you after a south wind?” Yes, said Denham, explaining that he was far from home and alone. No, retorted one of the women, you are an infidel and a hyena who eats blacks. His only hope of becoming civilized, continued the women, was to marry a wife or two who would teach him to pray and wash “and never let him return amongst his own filthy race.”

Clapperton related similar encounters. After three of a governor’s wives examined his skin closely they “remarked, compassionately, it was a thousand pities I was not black, for I had then been tolerably good-looking.” When he asked one of them, “a buxom young girl of fifteen, if she would accept of me for a husband . . . She immediately began to whimper; and on urging her to explain the cause, she frankly avowed she did not know how to dispose of my white legs.”

Sheikh al-Kanemi

Some Africans suspected Denham and Clapperton of being monsters and cannibals—another inversion of common white attitudes about blacks. No wonder that when Sheikh al-Kanemi, the ruler of Bornu, publicly shook hands with Denham and Clapperton, his courtiers gasped at his bravery for touching these mutants. Another inversion.

Barth and his companions ran into the same things. When the young boy Dorugu first saw Overweg, who bought and freed him, Dorugu was appalled that Overweg’s “face and hands were all white like paper,” and he feared that this stranger was going to eat him.

James Richardson

After months of travel Barth turned as dark as an Arab (and eventually passed himself off as a Syrian sherif). But Richardson disliked the sun and was careful to keep his skin pale. Consequently he often attracted laughing crowds and was sometimes advised to let his skin darken so he wouldn’t look so disgustingly white—a telling inversion of the old advertisements once aimed at dark-skinned people to improve their looks by bleaching their skin.