When my grandfather wanted to signify something far out of reach or unimaginably far away, the thing or person would be “way out in Timbuktu” or “gone to Timbuktu.” As a child I loved the word’s percussive sound and exotic aura. (For similar purposes he used a musical word that I heard as “Pulchapeck,” which I assumed was another of his fanciful coinages. Decades later while studying an atlas–a favorite pastime–I was shocked to come across Chapultepec. It turned out to be the site of a once-famous battle between U.S. and Mexican troops in 1847, probably the origin of my grandfather’s usage.)

Mansa Musa holding a nugget of gold, from a 1375 Catalan Atlas of the known world

It was years before I learned that Timbuktu existed outside his imagination. I also learned that for centuries of Western history, the imagination had been Timbuktu’s main location. The cause was probably Mansa Musa, emperor of Mali, who once ruled the city. In 1324 he made a haj across Africa through Cairo to Mecca. He traveled with an enormous caravan, including 80 camels that carried 300 pounds of gold each. Along the way he freely lightened these camels, especially in Cairo. Soon Europe was abuzz with rumors about golden cities in the heart of the Sahara. This chimera refused to die for more than five centuries, and many Europeans would die pursuing it.

Title page of Leo Africanus’s book about Africa

Meanwhile African travelers, traders, and scholars streamed through Timbuktu. A few left tantalizing reports. The restless Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta visited around 1352 and wrote a short account that mentioned gold and many naked women. Leo Africanus, a Spanish Moor, reached the city around 1510 and was impressed by the number of scholars and gold plates. Then in 1591 the king of Morocco sent an army that conquered and looted Timbuktu, and marched its scholars to Morocco in chains. To Europe, the place seemed to go dark.

After a few quiet centuries, Europe’s interest in Timbuktu reawakened, and the race to reach it was on. In 1824 the French Société de Géographie offered 10,000 francs to anyone who made it to the city and returned alive. The British were determined to beat the French. Most of the contestants didn’t survive the race.

Alexander Gordon Laing

In the first half of the 19th century, only two Europeans reached Timbuktu. The first was Major Alexander Gordon Laing, who led a British expedition from Tripoli. After being viciously attacked by Tuaregs and left for dead in the middle of the desert, he somehow lashed himself on to Timbuktu, arriving in 1826. The Muslim fundamentalists who controlled the place were incensed that an infidel was polluting their holy city. After five weeks, Laing was expelled. Not far into the desert, his guides murdered him and burned his journals.

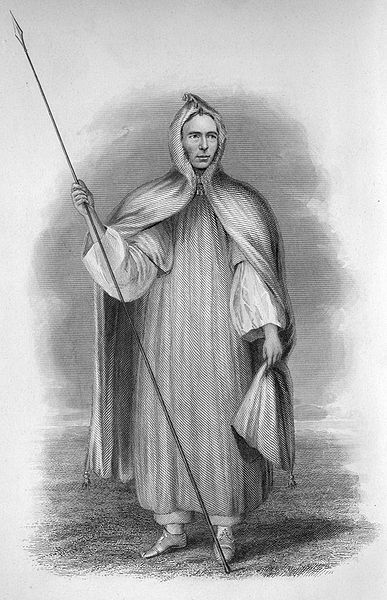

René Caillié

A year and a half later, in 1828, another European sneaked into Timbuktu disguised as a poor Muslim traveler. His name was René Caillié, a French dreamer inspired by Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. Everything about Caillié’s story defies belief: the years of sacrifice in preparation for the journey to Timbuktu, the horrible afflictions suffered en route and on the way home, the adulation and bestsellerdom followed by humiliation and poverty. He stayed in Timbuktu undetected for two weeks—after hearing about Laing, he decided not to dawdle—but he did return to Europe and collect the prize money, to the dismay of the British.

Twenty-five years passed before another European, also in disguise, dared to enter Timbuktu: Heinrich Barth.

He also enjoyed the market’s roasted locusts, still a valued source of protein in sub-Saharan Africa. Barth called the taste “agreeable.” Many African explorers reviewed the dish.

He also enjoyed the market’s roasted locusts, still a valued source of protein in sub-Saharan Africa. Barth called the taste “agreeable.” Many African explorers reviewed the dish.

Similar “sounds-like” spellings occurred when explorers asked Africans the name of some river or mountain. The confusion was further complicated because different peoples in Africa spoke unrelated languages, and naturally had different names for the same places, tribes, landmarks, plants, and animals. Travelers brought all the different words home and put them onto maps and into accounts and letters.

Similar “sounds-like” spellings occurred when explorers asked Africans the name of some river or mountain. The confusion was further complicated because different peoples in Africa spoke unrelated languages, and naturally had different names for the same places, tribes, landmarks, plants, and animals. Travelers brought all the different words home and put them onto maps and into accounts and letters.

I dished a lot of dash in

I dished a lot of dash in

The keeper offered to show us the former boundaries of the old royal city. We drove about a mile into the empty countryside west of town. The keeper said all this had once been inside the walls. We stopped where a low broken wall surrounded a tall

The keeper offered to show us the former boundaries of the old royal city. We drove about a mile into the empty countryside west of town. The keeper said all this had once been inside the walls. We stopped where a low broken wall surrounded a tall  Barth mentions that Sheikh al-Kanemi supposedly built his new capital at Kukawa because of a young baobab there. The keeper told us a refinement of this local legend: the tree inside the broken wall had been a sapling when the adolescent al-Kanemi used to lean against it and dream of glory—that’s why he later sited his capital here. This pleasing story was flawed only by impossibility; al-Kanemi spent his boyhood far from Kukawa.

Barth mentions that Sheikh al-Kanemi supposedly built his new capital at Kukawa because of a young baobab there. The keeper told us a refinement of this local legend: the tree inside the broken wall had been a sapling when the adolescent al-Kanemi used to lean against it and dream of glory—that’s why he later sited his capital here. This pleasing story was flawed only by impossibility; al-Kanemi spent his boyhood far from Kukawa. I asked him if he had ever heard of Barth. Yes, he said, his father and grandfather knew stories about the explorer, but he himself knew little beyond the name. He had no idea where Barth’s house had stood in old Kukawa. And anyway, he added, Rabih had destroyed it.

I asked him if he had ever heard of Barth. Yes, he said, his father and grandfather knew stories about the explorer, but he himself knew little beyond the name. He had no idea where Barth’s house had stood in old Kukawa. And anyway, he added, Rabih had destroyed it.

The two Nasirus rarely got the chance for a boat ride. Nasiru Wada paid the boatman an extra 200 naira, about $1.50, to do some fast spins. Nasiru Datti, landlubberly stiff, shook his head in disapproval.

The two Nasirus rarely got the chance for a boat ride. Nasiru Wada paid the boatman an extra 200 naira, about $1.50, to do some fast spins. Nasiru Datti, landlubberly stiff, shook his head in disapproval. The nomads at the muddy pond were Arabs from

The nomads at the muddy pond were Arabs from  A boy and a small girl in a multicolored robe stood behind the herd. The girl was a dynamo, scolding the camels in a shrill voice and whacking their legs with a stick if they tried to stray.

A boy and a small girl in a multicolored robe stood behind the herd. The girl was a dynamo, scolding the camels in a shrill voice and whacking their legs with a stick if they tried to stray.

The thatched roofs changed from the bowl-shaped design of the

The thatched roofs changed from the bowl-shaped design of the  Many twists and turns later, a couple of miles out of town, we reached a row of boats painted with geometric designs, on the shore of what appeared to be a river about 50 yards wide. In fact it was one of the myriad reed-flanked channels that constitute Lake Chad. When Barth saw the lake’s marshy waterways and tall reeds, he realized that one of the mission’s tasks would be impossible: to map Lake Chad’s borders. The boundaries between land and water were indistinct and changed each season. He saw large numbers of waterfowl, crocodiles, and hippopotamuses.

Many twists and turns later, a couple of miles out of town, we reached a row of boats painted with geometric designs, on the shore of what appeared to be a river about 50 yards wide. In fact it was one of the myriad reed-flanked channels that constitute Lake Chad. When Barth saw the lake’s marshy waterways and tall reeds, he realized that one of the mission’s tasks would be impossible: to map Lake Chad’s borders. The boundaries between land and water were indistinct and changed each season. He saw large numbers of waterfowl, crocodiles, and hippopotamuses.

Lake Chad’s labyrinthine channels still provide excellent cover for smugglers and illegal immigrants–the lake touches Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon, and Chad–so entry-points like Baga are filled with security personnel. Though the shoreline was crowded with people selling and socializing, our arrival immediately drew the attention of the marine police, the regular police, soldiers, customs officials, and immigration officers. To deflect suspicion, I presented myself as a historian, not a journalist. Their questions soon moved from wary to curious and friendly. The Nigerian “underwear bomber” had recently been nabbed while trying to blow up a U. S. airliner, igniting dark mistrust of Nigerians in America. The paranoia went in both directions: Nasuri Wada later told me that the lake authorities at first suspected me of being a CIA agent.

Lake Chad’s labyrinthine channels still provide excellent cover for smugglers and illegal immigrants–the lake touches Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon, and Chad–so entry-points like Baga are filled with security personnel. Though the shoreline was crowded with people selling and socializing, our arrival immediately drew the attention of the marine police, the regular police, soldiers, customs officials, and immigration officers. To deflect suspicion, I presented myself as a historian, not a journalist. Their questions soon moved from wary to curious and friendly. The Nigerian “underwear bomber” had recently been nabbed while trying to blow up a U. S. airliner, igniting dark mistrust of Nigerians in America. The paranoia went in both directions: Nasuri Wada later told me that the lake authorities at first suspected me of being a CIA agent.