For the last three years of his journey, from Kukawa to Timbuktu and back, and then on to Tripoli, Barth was accompanied by two young African boys as servants. When he left for home, he took them with him. One scholar has suggested that they were the first northern Nigerians to visit Europe. Their names were Abbega and Dorugu, and their story casts a fascinating sidelight onto Barth’s.

Abbega & Dorugu

Both boys became attached to the expedition as servants of Adolf Overweg, Barth’s fellow German scientist. Overweg bought them as slaves and immediately freed them. Abbega’s early history is sketchy. We know that he came from the Marghi tribe and had been stolen and sold into slavery. When he entered Overweg’s service, he was about 15.

We know more about Dorugu, who was several years younger, because he later told his story to a missionary/linguist who wrote it all down (more on that later). Dorugu was born in a Hausa village about fifty miles southwest of Zinder in present-day Niger. Like Abbega, he was seized in a raid and sold into slavery. His Kanuri master took him to Kukawa, where he was sold to an Arab to pay a debt. This was around 1851 when Dorugu was 11 or 12.

The following year, as Overweg and Barth prepared for their excursion with the rapacious Welid Sliman, Overweg hired Dorugu from the Arab as a camel boy. Overweg must have gotten attached to him, because when they returned, the scientist bought the boy and freed him. Dorugu, little more than a child, stayed with Overweg as a servant.

When Overweg died, Barth assured the two distraught boys that he would take care of them, and they stayed with him for the rest of the expedition. By the time they all returned to the journey’s starting point in Tripoli, Abbega was about 18, Dorugu about 15.

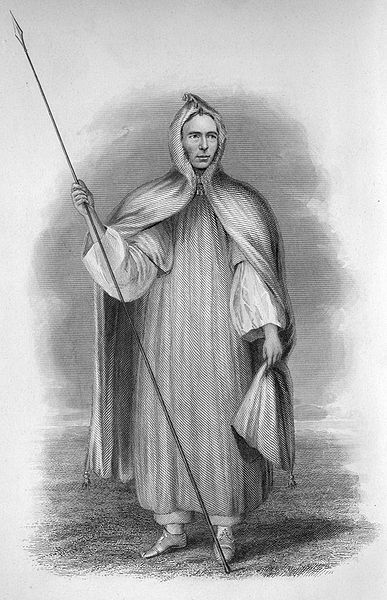

Barth’s invitation to accompany him to Europe must have struck them as a wonderful prospect, made more exciting by the fancy clothes Barth bought for them: trousers of blue wool, tailored jackets of red wool with metal buttons and gold stripes, red wool caps with blue silk tassels. Barth hoped that training in English and other skills would make them useful to future explorers in Africa. He also planned to get linguistic help from them for a book on African languages he intended to write after publishing his journal.

Abbega & Dorugu

Everything about the trip to London amazed the teenagers—the steamer to Malta and Marseilles, the huge smoking iron carriage that sped across France, the strange implements called forks, the complete absence of sand, the chalk-faced women with waists like wasps’.

In early 1856, after a short trip to see Barth’s family in Germany, they returned to London. Barth got to work on Travels and Discoveries. He arranged for the Africans to stay with Reverend J. F. Schön, a missionary who had been on the disastrous Niger expedition of 1841. Schön was also compiling a Hausa dictionary, so Barth knew that Dorugu could be useful to him. Schön interviewed Dorugu extensively about his young life. (The result can be found in West African Travels and Adventures, edited by Anthony Kirk-Greene and Paul Newman.)

While tutoring both boys, Schön also proselytized them, with the goal of sending them back to Africa as missionaries. They were baptized in May 1857. Dorugu was christened James Henry, after Schön and Barth. Abbega was named Frederick Fowell Buxton, after Schön and T. Fowell Buxton, an evangelical abolitionist who convinced the British government to fund the 1841 Niger expedition, and who fervently believed that pagan Africa would be redeemed by “Bible and plough.”

Meanwhile the two boys had become terribly homesick and asked Barth to get them back to Africa. He set about convincing the Foreign Office to pay their return voyage to Tripoli, and arranging with the British consul there to provide them with a camel, a guide to Kano, and the Arabic passports carried by free blacks in defense against slavers.

Anti-Slavery Society Convention, 1840, by Benjamin Robert Haydon. Buxton at upper left

Next came two kicks to Barth’s head. The Anti-Slavery Society, a powerful force in Britain, accused him of joining in the slave trade while in Africa and of transporting two young slaves to England—Abbega and Dorugu. The source of these scandalous lies may have been a British soldier who had briefly traveled with Barth at the end of his journey and was now seeking revenge for the explorer’s less-than-stellar report about him to the Foreign Office. The accusations stunned and infuriated Barth.

The second kick came when Abbega and Dorugu suddenly informed him they now wanted to stay in England. Barth, angry that his good intentions for them had blown up in his face and that all his labors to get them safely home were now being shrugged off, refused this change of plans—which he had no right to do—and instructed them to take the appointed ship from Southampton. The boys did briefly board, but then disembarked with Schön and went home with him. Barth considered this a betrayal by both the Africans and Schön, whom he accused of hijacking the teenagers for his own purposes.

Abbega left England for Africa later that same year. Dorugu stayed for eight years before going back. Both quickly dropped missionary work; there were more lucrative ways to use their new skills. Dorugu eventually became a schoolteacher. Abbega reverted to Islam and became an interpreter for explorers, British officials, and the Royal Niger Company.

Many years later, when Britain had taken over Nigeria, the colonial government wanted to recover the remains of Overweg, who had died in Britain’s service. For help, they turned to a chief named Maimana—Abbega’s grandson. Maimana went to the village on Lake Chad where Overweg had died and located an 80-year-old woman who knew the gravesite. The British dug and found Overweg’s bones. They were taken to Maiduguri, the new regional capital of Bornu, and now rest in the small European cemetery there.

The keeper offered to show us the former boundaries of the old royal city. We drove about a mile into the empty countryside west of town. The keeper said all this had once been inside the walls. We stopped where a low broken wall surrounded a tall

The keeper offered to show us the former boundaries of the old royal city. We drove about a mile into the empty countryside west of town. The keeper said all this had once been inside the walls. We stopped where a low broken wall surrounded a tall  Barth mentions that Sheikh al-Kanemi supposedly built his new capital at Kukawa because of a young baobab there. The keeper told us a refinement of this local legend: the tree inside the broken wall had been a sapling when the adolescent al-Kanemi used to lean against it and dream of glory—that’s why he later sited his capital here. This pleasing story was flawed only by impossibility; al-Kanemi spent his boyhood far from Kukawa.

Barth mentions that Sheikh al-Kanemi supposedly built his new capital at Kukawa because of a young baobab there. The keeper told us a refinement of this local legend: the tree inside the broken wall had been a sapling when the adolescent al-Kanemi used to lean against it and dream of glory—that’s why he later sited his capital here. This pleasing story was flawed only by impossibility; al-Kanemi spent his boyhood far from Kukawa. I asked him if he had ever heard of Barth. Yes, he said, his father and grandfather knew stories about the explorer, but he himself knew little beyond the name. He had no idea where Barth’s house had stood in old Kukawa. And anyway, he added, Rabih had destroyed it.

I asked him if he had ever heard of Barth. Yes, he said, his father and grandfather knew stories about the explorer, but he himself knew little beyond the name. He had no idea where Barth’s house had stood in old Kukawa. And anyway, he added, Rabih had destroyed it.

The two Nasirus rarely got the chance for a boat ride. Nasiru Wada paid the boatman an extra 200 naira, about $1.50, to do some fast spins. Nasiru Datti, landlubberly stiff, shook his head in disapproval.

The two Nasirus rarely got the chance for a boat ride. Nasiru Wada paid the boatman an extra 200 naira, about $1.50, to do some fast spins. Nasiru Datti, landlubberly stiff, shook his head in disapproval. The nomads at the muddy pond were Arabs from

The nomads at the muddy pond were Arabs from  A boy and a small girl in a multicolored robe stood behind the herd. The girl was a dynamo, scolding the camels in a shrill voice and whacking their legs with a stick if they tried to stray.

A boy and a small girl in a multicolored robe stood behind the herd. The girl was a dynamo, scolding the camels in a shrill voice and whacking their legs with a stick if they tried to stray.

The thatched roofs changed from the bowl-shaped design of the

The thatched roofs changed from the bowl-shaped design of the  Many twists and turns later, a couple of miles out of town, we reached a row of boats painted with geometric designs, on the shore of what appeared to be a river about 50 yards wide. In fact it was one of the myriad reed-flanked channels that constitute Lake Chad. When Barth saw the lake’s marshy waterways and tall reeds, he realized that one of the mission’s tasks would be impossible: to map Lake Chad’s borders. The boundaries between land and water were indistinct and changed each season. He saw large numbers of waterfowl, crocodiles, and hippopotamuses.

Many twists and turns later, a couple of miles out of town, we reached a row of boats painted with geometric designs, on the shore of what appeared to be a river about 50 yards wide. In fact it was one of the myriad reed-flanked channels that constitute Lake Chad. When Barth saw the lake’s marshy waterways and tall reeds, he realized that one of the mission’s tasks would be impossible: to map Lake Chad’s borders. The boundaries between land and water were indistinct and changed each season. He saw large numbers of waterfowl, crocodiles, and hippopotamuses.

Lake Chad’s labyrinthine channels still provide excellent cover for smugglers and illegal immigrants–the lake touches Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon, and Chad–so entry-points like Baga are filled with security personnel. Though the shoreline was crowded with people selling and socializing, our arrival immediately drew the attention of the marine police, the regular police, soldiers, customs officials, and immigration officers. To deflect suspicion, I presented myself as a historian, not a journalist. Their questions soon moved from wary to curious and friendly. The Nigerian “underwear bomber” had recently been nabbed while trying to blow up a U. S. airliner, igniting dark mistrust of Nigerians in America. The paranoia went in both directions: Nasuri Wada later told me that the lake authorities at first suspected me of being a CIA agent.

Lake Chad’s labyrinthine channels still provide excellent cover for smugglers and illegal immigrants–the lake touches Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon, and Chad–so entry-points like Baga are filled with security personnel. Though the shoreline was crowded with people selling and socializing, our arrival immediately drew the attention of the marine police, the regular police, soldiers, customs officials, and immigration officers. To deflect suspicion, I presented myself as a historian, not a journalist. Their questions soon moved from wary to curious and friendly. The Nigerian “underwear bomber” had recently been nabbed while trying to blow up a U. S. airliner, igniting dark mistrust of Nigerians in America. The paranoia went in both directions: Nasuri Wada later told me that the lake authorities at first suspected me of being a CIA agent.

The morning was beautiful–soft breezes, 70 degrees. “A bit cold,” complained Nasiru Datti. When we left Nguru nearly two hours later, the woman was still pounding millet. Her child still dozed on her back, lulled by a rhythm as strong, familiar, relentless, and fundamental as his mother’s heartbeat.

The morning was beautiful–soft breezes, 70 degrees. “A bit cold,” complained Nasiru Datti. When we left Nguru nearly two hours later, the woman was still pounding millet. Her child still dozed on her back, lulled by a rhythm as strong, familiar, relentless, and fundamental as his mother’s heartbeat.

The thought that rings through these like a chorus is “neglect.” No one tended Barth’s low flame more faithfully than A. H. M. Kirk-Greene. He became fascinated by Barth while serving as a British district officer in northeastern Nigeria (Adamawa and Bornu) before going on to an eminent academic career at Oxford. Between the late 1950s and early 1970s he wrote half a dozen enlightening essays about the explorer. He also persuaded Oxford to publish

The thought that rings through these like a chorus is “neglect.” No one tended Barth’s low flame more faithfully than A. H. M. Kirk-Greene. He became fascinated by Barth while serving as a British district officer in northeastern Nigeria (Adamawa and Bornu) before going on to an eminent academic career at Oxford. Between the late 1950s and early 1970s he wrote half a dozen enlightening essays about the explorer. He also persuaded Oxford to publish