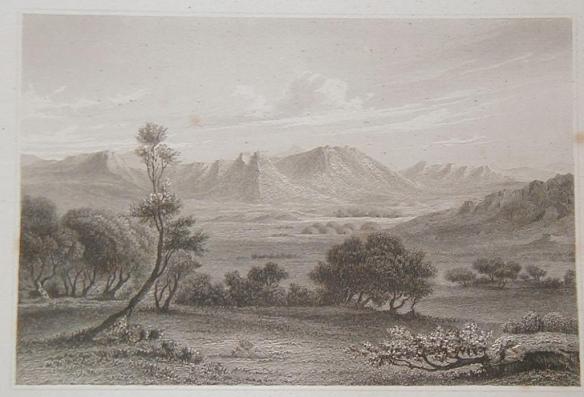

One of the most fascinating and perilous segments of Barth’s journey occurred in the district of Aïr in the Sahara, in present-day Niger. About 300 miles long and 200 miles wide, Aïr consists of steep disconnected massifs and volcanic cones, some rising more than 6,000 feet from the desert floor. Barth called it “the Switzerland of the desert.” Until he described it, Europeans were unaware that the Sahara contained such landscapes. Before Barth’s party entered the region, no European had ever set foot there. European visitors would be extremely rare for many decades afterwards.

The landscape of Aïr. From Travels and Discoveries.

In Barth’s day, Aïr was an isolated redoubt occupied by gangs of Tuareg brigands who had never been subdued by an outside power. This remained true, off and on, for next 150 years. I had hoped to visit Aïr while researching my book, but the district was off-limits to travelers because Tuareg rebels had a base there.

At the time of Barth’s journey, the capital of Aïr was Tintellust, deep in the region’s heart. Barth’s group reached there soon after being plundered and nearly murdered by Tuaregs in Aïr. The Europeans expected Tintellust to be a city, but it turned out to be a village of 250 dwellings shaded by trees in a pleasant mountain valley. The explorers weren’t too disappointed, because for the first time in weeks they felt safe. Tintellust was the home of Sultan Annur, leader of the Kel Owis, a Tuareg tribe. For a large sum, Annur agreed to protect the expedition.

Annur told the Christians to camp at a spot 800 yards from the village on some sand hills. The location offered sweeping views of the valley and the mountains. Barth predicted that the place would henceforth be called the “English Hill” or the “Hill of the Christians.”

Tintellust

Francis Rennell Rodd, a British explorer, traveled in Aïr in the 1920s and wrote a wonderful book about it called People of the Veil. Rodd found Aïr and its Tuareg inhabitants exactly as Barth had described them 75 years earlier. I especially like Rodd’s description of male Tuaregs: “The men never grow fat: they are hard and fit and dry like the nerve of a bow, or a spring in tension. Of all their characteristics the one I have most vividly in mind is their grace of carriage. The men are born to walk and move as kings, they stride along swiftly and easily, like Princes of the Earth, fearing no man, cringing before none, and consciously superior to other people.” Their belligerence and opportunism, noted Rodd, hadn’t changed either, as expressed in one of their sayings: “Kiss the hand you cannot cut off.”

Rodd wanted to visit Tintellust to look for traces of Barth, whom he called “perhaps the greatest traveler there has ever been in Africa.” Tintellust wasn’t on any map, but Rodd’s guide knew the village and took him there. As they reached the outskirts, the guide pointed out a place called “the House of the Christians.” When Rodd asked why, the guide said that in the olden days three white Christians who weren’t French had come to Tintellust—not as conquerors, like the French, but as friends of Chief Annur—so the thatch huts where they camped had never been inhabited or pulled down. All that remained of the camp, noted Rodd, were “the traces of two straw huts and a shelter, a wooden water trough, and some broken pots.”

In 2005 Julia Winckler, a British photographer and teacher fascinated by Barth, traveled to Tintellust. She too was shown Barth’s old encampment. She documented her visit to Tintellust (and Agadez) with photographs and videos: www.retracingheinrichbarth.co.uk. In Tintellust, according to Winckler, a story persists that Barth buried treasure nearby, and the villagers occasionally still dig for it. Barth would be amused–by the time he and his ragged group reached Tintellust, they had been pillaged several times and had no surplus to bury.

The nomads at the muddy pond were Arabs from

The nomads at the muddy pond were Arabs from  A boy and a small girl in a multicolored robe stood behind the herd. The girl was a dynamo, scolding the camels in a shrill voice and whacking their legs with a stick if they tried to stray.

A boy and a small girl in a multicolored robe stood behind the herd. The girl was a dynamo, scolding the camels in a shrill voice and whacking their legs with a stick if they tried to stray.

The thatched roofs changed from the bowl-shaped design of the

The thatched roofs changed from the bowl-shaped design of the  Many twists and turns later, a couple of miles out of town, we reached a row of boats painted with geometric designs, on the shore of what appeared to be a river about 50 yards wide. In fact it was one of the myriad reed-flanked channels that constitute Lake Chad. When Barth saw the lake’s marshy waterways and tall reeds, he realized that one of the mission’s tasks would be impossible: to map Lake Chad’s borders. The boundaries between land and water were indistinct and changed each season. He saw large numbers of waterfowl, crocodiles, and hippopotamuses.

Many twists and turns later, a couple of miles out of town, we reached a row of boats painted with geometric designs, on the shore of what appeared to be a river about 50 yards wide. In fact it was one of the myriad reed-flanked channels that constitute Lake Chad. When Barth saw the lake’s marshy waterways and tall reeds, he realized that one of the mission’s tasks would be impossible: to map Lake Chad’s borders. The boundaries between land and water were indistinct and changed each season. He saw large numbers of waterfowl, crocodiles, and hippopotamuses.

Lake Chad’s labyrinthine channels still provide excellent cover for smugglers and illegal immigrants–the lake touches Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon, and Chad–so entry-points like Baga are filled with security personnel. Though the shoreline was crowded with people selling and socializing, our arrival immediately drew the attention of the marine police, the regular police, soldiers, customs officials, and immigration officers. To deflect suspicion, I presented myself as a historian, not a journalist. Their questions soon moved from wary to curious and friendly. The Nigerian “underwear bomber” had recently been nabbed while trying to blow up a U. S. airliner, igniting dark mistrust of Nigerians in America. The paranoia went in both directions: Nasuri Wada later told me that the lake authorities at first suspected me of being a CIA agent.

Lake Chad’s labyrinthine channels still provide excellent cover for smugglers and illegal immigrants–the lake touches Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon, and Chad–so entry-points like Baga are filled with security personnel. Though the shoreline was crowded with people selling and socializing, our arrival immediately drew the attention of the marine police, the regular police, soldiers, customs officials, and immigration officers. To deflect suspicion, I presented myself as a historian, not a journalist. Their questions soon moved from wary to curious and friendly. The Nigerian “underwear bomber” had recently been nabbed while trying to blow up a U. S. airliner, igniting dark mistrust of Nigerians in America. The paranoia went in both directions: Nasuri Wada later told me that the lake authorities at first suspected me of being a CIA agent.