In the 1830s the German philosopher G. H. F. Hegel remarked that Africa “is no historical part of the world; it has no movement or development to exhibit.”

Poof! An entire continent’s history dismissed with a philosophical snap. Even if Hegel “loses a lot in the original,” as one wit put it, this is breath-taking arrogance bred of ignorance. In Barth’s era it was also typical. The common wisdom, to misuse the word, was that Africa had no history worth considering. The continent was deemed illiterate, uncivilized, ungoverned, unshaped, a place of dark chaos. Egypt? An exception that proved the rule, sniffed Hegel, since it had been settled by lighter-skinned Semites.

Africans had a different point of view, easily discovered by anyone willing to look. Though information about the continent was extremely sketchy and often wrong, Roman and Muslim historians and travelers such as Pliny the Elder, Ibn Battuta, Leo Africanus, Al-Bakri, and Al-Idrisi had told bits of Africa’s story for centuries. More recent explorers such as Mungo Park, Friedrich Hornemann, Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, Hugh Clapperton, and Dixon Denham had sprinkled their narratives with anecdotes about learned Africans and African history. But the public tended to overlook these reports, preferring the ones that were exotic, lurid, and violent—the ones that confirmed their assumptions.

Barth had been trained by professors influenced by Hegel and wasn’t immune to the age’s racial preconceptions. But he also had steeped himself in the old and new accounts about Africa, and he had already seen part of Africa firsthand during a three-year, three-continent journey along the shores of the Mediterranean. He had glimpsed an African reality that differed from European assumptions about it.

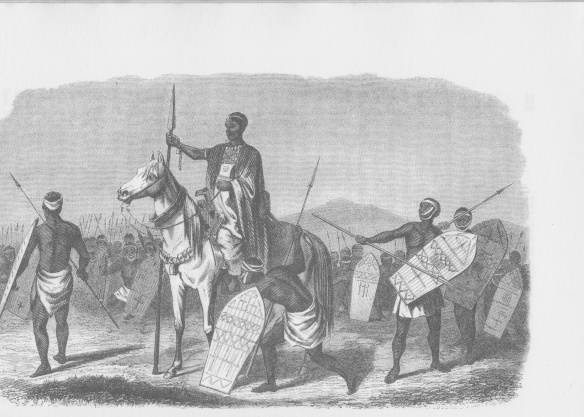

He was also a scientist who tried to keep an open mind and follow the evidence before him. Part of what Barth discovered on his journey—what he was willing to let himself discover—was that Africa had a long rich history, some of it written, that was unsuspected or ignored in Europe. He recorded barbarity and fanaticism, but also scholarship, governance, culture, tradition. His work should have demolished the canard that Africa had none of these virtues. But Barth’s news wasn’t heard on the eve of imperialism in Africa, nor in the following decades.

More than a century after his journey, the idea that Africa had no history was still alive and writhing in respectable circles. “Perhaps in the future there will be some African history to teach,” said the Oxford historian Hugh Trevor-Roper in 1963. “But at the present there is none; there is only the history of Europeans in Africa. The rest is darkness, and darkness is not the subject of history.”

Ignorance is a recurring virus. Barth believed it could be cured by science and knowledge, but it’s a wily pestilence with no fool-proof antidote.

Pingback: Lost and Found: the Treasures of Timbuktu | In the Labyrinth